Does the Super Bowl have a trafficking problem?

- Sabrina Thulander

- Feb 9, 2018

- 5 min read

For all of its profitability, the NFL is plagued with problems. Domestic violence, sexual misconduct, and life threatening head injuries are just a few of the themes that grace the headlines at the beginning of each season. Although these issues have exposed some difficult realities of sports, masculinity, and sex in America, many of the systematic problems underlying the success of the League remain to be seen. One such issue is the occurrence of human trafficking during its most popular event– the Super Bowl.

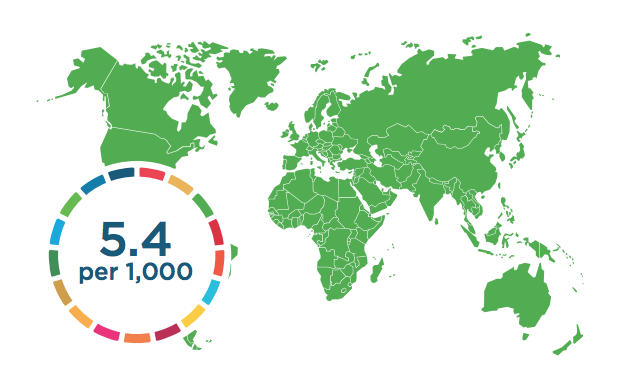

According to Alliance 8.7, 5.4 out of every 1,000 people on earth are victims of trafficking and modern slavery. Image credit Alliance 8.7

Human trafficking, defined by the Department of Homeland Security as modern-day slavery that “involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act,” affected 40.3 million people on any given day in 2016. What makes human trafficking unique among global crime is that the perpetrators do not discriminate against class, race, religion, age, gender, or location. It is a crime with no social, geographical, or economic restrictions, which helps its executors and their victims stay invisible.

While human trafficking includes forced marriage and forced labor, in the context of the Super Bowl it is usually discussed strictly on the basis of sexual exploitation. Recently, there have been several stories released from Sports Illustrated (SI), Vice, and local news organizations about potential upticks in human trafficking activity during the Super Bowl (though the topic has not yet been thoroughly investigated by any major news sources). Most of these stories combat the idea that the Super Bowl causes an increase in human trafficking crime, citing a 2011 report by the Global Alliance Against Trafficking Women that concluded there is no evidence to support the claim. The report states that the resurrection of human trafficking news around the Super Bowl each year is more related to the agendas of the organizations reporting it, such as anti-immigration or anti-prostitution sentiments. This results in high levels of action by law enforcement in host cities during the event.

Data from the McCain Institute for International Leadership shows an increase in online sex ads in Phoenix from 2014 to 2015, the city’s host year.

Also used to combat the “myth” of human trafficking is the fact that, based on police records and increased police activity on Super Bowl Sunday, there are no clear statistics showing an increase in sex crimes arrests in host cities. This is an ineffective variable by which to measure, however, as we have seen from the research on race, police and crime, increased police presence does not automatically equal greater safety or lower crime rates. Furthermore, across the U.S. in 2017, over the Super Bowl weekend there were more than 750 arrests for sex trafficking. Taking into account that for each arrest there are at least as many victims, no increase in arrests in host cities year to year does not show the success of law enforcement at preventing sex crimes, but rather shows its continued failure to protect victims.

Two questions arise in response to these articles. First, in each piece, human trafficking activity is only monitored in the host city. The Super Bowl is a international event, however, and is broadcasted in all 50 states and in 180 countries. Like human trafficking itself, the Super Bowl does not have any geographical boundaries. As the world’s most profitable sporting event brand, the Super Bowl (and Super Bowl parties across the country) attracts major business people, athletes, and millionaires of other means to congregate. Commercial sex acts are not uncommon in gatherings of wealthy people, so why do the available reports focus only on host cities? The potential for sex trafficking exists everywhere the Super Bowl is broadcasted.

Second, and more deeply, if it is taken for truth that the Super Bowl does not cause an increase in human trafficking activity, why doesn’t it and why do we expect it to? Why is there this seemingly unbreakable link between the sexual exploitation of trafficked humans and the glamour and extravagance of the Super Bowl? The answer to this seems purely societal. Blame it on Hollywood or on experience, but there is little doubt there is a cognitive link between wealthy men and sexual exploitation, paid or not.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that these reports are correct and the Super Bowl does not actually contribute to a spike in sex trafficking activity in the host city or nation wide. Vice and SI seem to point to statements by former Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott, who boldly stated that the Super Bowl is the “single largest human trafficking incident in the United States,” as the soundbite that keeps the media coming back to this story. Although the available evidence says otherwise, there is something instinctive about the association of the two. As the momentum for movements like #MeToo and Time’s Up continues to grow, the topic of power abuses by men is on the minds of many in our society. It would come as a surprise if one of the most hyper-masculinized events in the U.S. did not further contribute to the abuse of power in a sexual manner. The continued reveal of lived experiences by women across the world, and the unspoken acknowledgement that these types of abuses happen behind closed doors, is one reason the rumor around the Super Bowl and sex trafficking persists.

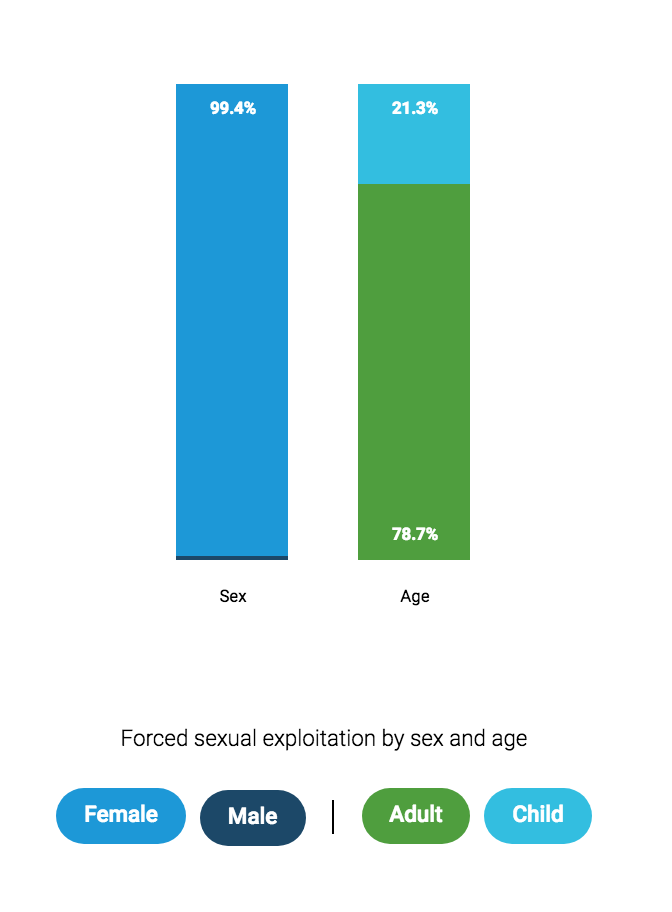

Alliance 8.7 data demonstrates the some demographics of global sex trafficking victims. Image credit: Alliance 8.7

We know a lot about human trafficking in its beginning stages– the who, why, and how of the industry. What we lack is significant study on middle and end stages– the where, when, and what. Where, especially during high profile events, are we most likely to find victims or evidence of human trafficking? When are victims transported to the location of their exploitation relative to the time of the event? Under what circumstances do victims escape and would they be willing to aid in investigations? This lack of research, especially as it pertains to sex trafficking, is not just restricted to the Super Bowl, but is a problem faced by human trafficking researchers worldwide. On only a few occasions have human trafficking crimes been documented and studied as a part of mega events, such as the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, or the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. In both of these cases, the research is almost exclusive to labor abuses. Only the McCain Institute for International Leadership has conducted research on commercial sexual exploitation and the Super Bowl. It is irresponsible, then, to claim that the Super Bowl does not contribute to sex trafficking when there is no evidence to support either argument.

Human trafficking is a serious global crime, and one thing the coverage of sex crimes and the Super Bowl thus far is right on is that creating false myth around the issue does more damage than it creates help for the actual victims of trafficking. The argument here is simply that the standards by which we measure the rate of trafficking during the Super Bowl, predominantly by the number of arrests and police presence, is insufficient to calculate the actual rate of crime taking place. Human trafficking crimes at the Super Bowl, like all other global trafficking crime, is protected by its indefiniteness. In order to more deeply understand and identify trafficking, both during sporting events and more widely, new standards of measurement and prevention must be implemented, including a rigorous look at the societal roots of sex trafficking. Until this happens, we cannot know for certain whether or not the Super Bowl has a human trafficking problem.

***This article was originally posted on Sabrina Thulander's Medium page and is posted with the permission of the author.