Contributions from: Marilisa Dolci, Marie Bellanger and Robyn Lewis

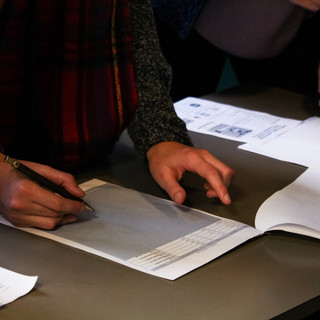

UN House Scotland, in collaboration with: UNESCO, Link Community Development International, Gaia Education and the Scottish Malawi Partnership, hosted the launch event for the Global Education Monitoring Report in Edinburgh on 24th October 2016.

In the opening address, Dr. Gari Donn, executive director of UNHS, set out that UNHS is actively working to strengthen, promote and engage Scottish civil society with all seventeen of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) through seminars, meetings and conferences. In November, UNHS held a Gender Equality Conference addressing female empowerment (SDG5) and in March 2016, a seminar was held on Climate Change (SDG13).

Dr. Donn praised the speakers, who complimented each other in their discussions of the goals, measurement methods and the reality on the ground, and was pleased to note that the event coincided with UN Day.

The Sustainable Development Goals set out in the United Nations “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” cover a range of core issues affecting people across the globe, from sanitation and wellbeing to marine life. Secretary-General, Ban Ki-Moon, commented: “The new agenda is a promise by leaders to all people everywhere. It is an agenda for people, to end poverty in all its forms – an agenda for the planet, our common home.”

Alasdair McWilliams’ opened the event by outlining the complexities of the SDG 4 proposals. Complexities, which are to be expected of a project attempting to reform education at primary, secondary, higher and lifelong level education across the world.

Professor Kenneth King then briefly summarised the history of UN education developments and tracked the inclusion of quality in implementation guidelines. He analysed the process of translating the delicately constructed goals into succinct indicators for measurement and criticised this simplification.

Dr. Samantha Ross detailed the work of Link Community Development in sub-Saharan Africa, detailing their efforts to develop sustainable, community backed local education and support girls in completing their education.

Chief Executive at Gaia Education, May East, was unfortunately unable to contribute to the event as planned. Gaia Education provides sustainable education, with an eye to promote thriving communities, through face-to-face programmes, e-learning and project-based learning.

While all of the Speakers highlighted that there are many challenges ahead in achieving SDG4, the resounding tone of the evening was one of hope.

Chapter 1: GEM UNESCO SDG 4 Launch Presentation

Alasdair McWilliams opened the event by delivering a presentation on the Global Education Monitoring Report, which he was involved in writing. His presentation highlighted the main findings and focuses of the report.

Alasdair started his presentation by giving an overview of the SDG agenda and SDG 4. Indeed, a year ago, the Member States of the United Nations agreed on the new Sustainable Development Goals agenda. Each of the 17 goals has a specific target to be achieved over the next 14 years. The 4th SDG, on education, ensures inclusive and equality education and promotes lifelong learning opportunities for all. He emphasised that the SDG agenda is a universal agenda which is highly relevant for both rich and poor countries alike.

The GEM report is the first in a 15 year-series to mark the progress in education and the new agenda. The international community has come up with 11 global indicators to monitor progress on the 10 targets of SDG 4. Countries have committed to report information on each of those 11 indicators. The report therefore analyses each target and indicator in detail, identifying gaps where further work is needed. He reminded us, however, that it is important to note that many indicators have not yet been measured on a global scale, especially those related to learning outcomes.

Alasdair went on to present some findings from the monitoring of SDG4 according to the various targets, with recommendations for monitoring. For instance, in terms of target 4.1 (on universal completion of Primary and Secondary education by 2030) there were still 263 million children and youth out of school in 2014 and only 43% of youth had completed upper secondary school. In terms of target 4.5, on inequalities in education, gender disparities increased by education levels and vast gaps remain. For instance, in low income countries, for every 100 of the richest people, only 36 of the poorest youth complete primary education and only 7 complete secondary educations.

The report outlined 6 key steps that governments should follow to strengthen national monitoring of education in the next 3-5 years. He stressed that assessing the quality of education should not be reduced to measurable learning outcomes but should take into account curricula, textbook and teacher education programmes. Assessing quality will address tolerance, human rights and sustainability. He noted schooling alone cannot deliver all the outcomes necessary to improve education by 2030, we need to focus on learning throughout life and at present education opportunities for adults attract little funding and are barely monitored.

Before addresseing the intersection of education and the other SDGs, Alasdair noted that ambition must be matched by action if we are to move away from current trends. Indeed, the GEM report has assessed the likelihood of achieving the first target of universal education for primary and secondary completion by 2030. If past rates continue, not even universal primary completion will be achieved by 2030 and universal secondary completion will only be achieved by 2084. Sub Saharan Africa is even further behind and it is estimated it will not achieve the target until after the end of the century. Alasdair pointed out that we need a complete break with past trends if these commitments are to be fulfilled.

He then went on to talks about the other SDGs which cross cut into SDG 4. Indeed, the report also looks at the links between education and the remaining 16 goals. These are grouped into 6 chapters focusing on the planet, prosperity, people, peace, place and partnerships.

In terms of the planet, Alasdair mentioned the SDG agenda draws together those working on human development and environment for the first time. Indeed, education can support a shift to a more sustainable way of living and has proved a valuable tool for climate change awareness. Schools help students understand environmental problems and types of actions needed to address. Education also builds skills and discourages unsustainable practices. One key takeaway from the report is that if we are to start living in a more sustainable manner we must acknowledge that learning is not something that only happens in school. Beyond formal education, government agencies, religious organizations, non-profit and community groups, labour groups, and private sector can change collective behaviour.

In terms of prosperity, Alasdair emphasised that education plays a role in making production and consumption sustainable, supplying skills for the creation of a green industry and research towards innovation. Education can also protect people from poor employment conditions and working poverty. Interestingly, it is estimated that governments need to increase energy research and development by fivefold to achieve a quick transition to low carbon intensity. However, many countries have halted or reduced investment in agricultural research. Alasdair noted that education can help with this shift, giving the farmers’ knowledge and producing innovative agricultural research. Moreover, the report shows that if low income countries reach the target of universal secondary education by 2030, by 2050, per capita per youth will increase by 75% and 60 million will be lifted out of poverty.

When it comes to people, Alasdair reported that that inclusive social development requires universal provision of essential services such as education, health, water, sanitarian, energy, housing and transportation. Yet in low income countries, over 28% do not have access to sanitation facilities and 25% have access to electricity, significantly impeding education provision. Educating girls and women is at the heart of social development and UNESCO recognised that more educated mothers are more likely to seek help during pregnancy and childbirth and keep children in good health. He noted projections that if women in Sub-Saharan Africa achieved universal upper secondary education by 2030, it would prevent 3.5 million child deaths in 2050-2060. However, he noted that education on its own is not enough to achieve equality in society and ensure that all have access to most basic services. Education must be integrated with health and social protection programmes that seek to reduce vulnerability.

Preventing violence and achieving sustainable peace requires democratic and representative institutions as well as well-functioning justice systems and education is key method of expanding political participation and inclusive democracy. Education is also a powerful preventative tool to reduce violence and conflict. Alastair noted that countries with significant education gaps are more likely to endure conflict, yet of all the peace agreements set out between 1989 and 2005, almost one third made no mention of education at all. Equitable and quality education can give people the literacy and related skills to evaluate policies and campaign messages in political information. Indeed, across 102 countries, adults with tertiary education were 60% more likely to request information from government.

Urbanisation was discussed as one of today’s defining demographic trends. Over half the world lives in cities and in the coming decades, the majority of projected population growth will be in current cities and low income countries. Yet, as Alasdair noted, the education sector is largely excluded in key urban planning decisions. The report illustrates why education should be integrated in those decision making processes. Indeed, more than one third of current residents in poor countries live in slums or shelter house, characterised by poor access to education, especially public education. Teacher preparation and mentoring programmes, therefore, have the potential to discourage the discriminatory attitudes that exacerbate social marginalization and exclusion in cities across the world.

Finally, Alasdair noted that the report also pays special attention to partnerships and the importance of developing integrative approaches to solving collective problems. However, few countries have actually pushed for integrative action on budgets. Without strong political incentives and adequate financial backing, planning and implementation are unlikely to change significantly. Mobilising domestic resources is therefore critical and aid will be needed to help poorest countries reach targets. To reach the SDG goals, aid must be better aligned to help those in need, for instance, Chad only received 2 dollars per child in 2014 and 28% had completed primary school. Mongolia, by contrast, received 45 dollars per child and most children completed primary school.

Alasdair completed his presentation by focusing on the report’s policy recommendations on how education can contribute more effectively to sustainable development. An important emphasis throughout the report has been on stronger efforts at collaboration between ministries, experts and civil society at local and national levels and across sectors. Finance is also an important issue. Indeed, education systems need to increase predictable and equitable financing in universalised primary and secondary education completion. Lastly, Alasdair noted that there is a need to revisit the purpose of education. This includes examining the curricula, teaching methods and learning outcomes that are needed to achieve ambitious the 2030 agenda. Civic, peace and sustainability education programmes can be important levers for SDG progress, ensuring more equitable justice systems, less violence and more constructive societies. They also could increase understanding and links between culture, the economy and the environment.

Chapter 2: Professor Kenneth King

Kenneth King is an Emeritus Professor of the University of Edinburgh in both the School of Social and Political Science and in the Moray House School of Education. King is also extensively involved in the Network for International Policies and Cooperation in Education and Training (NORRAG), and edits their biannual publication NORRAG NEWS.

Professor King talked engagingly about whether the initial components of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have become lost in the translation of the goals to measurable indicators. He looked in particular at whether this had happened to the quality learning element of SDG 4.

King started by providing a history of quality within the discourse of education goals and targets. He showed that despite critiques of its absence, quality has actually featured in discussions on education before the creation of the SDGs. King explained that quality education had a place in the Education for All (EFA) agenda, adopted first at the World Conference on Education for All in Jomtien (1990) and developed at the World Education Forum in Dakar (2000). He pointed out that Dakar’s Expanded Commentary actually emphasised that “Quality is at the heart of learning,” although how to measure it was unclear at this stage.

As a second historical stream, King then looked at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCED) and its Development Assistant Committee’s (DAC’s), who created the International Development Targets (1996). These International Development Targets fed into the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) which saw “universal primary education in all countries by 2015” and “eliminating gender disparity in primary and secondary education by 2005” become the main focuses. Although the OCED-DAC emphasised quality would be essential in achieving these targets, qualitative factors appeared lost in the movement to the MDGs. King humorously remarked that quality was too difficult a concept for politicians. They instead sought measurable goals that were easier to understand.

Moving away from history and into the present, King explained that SDG 4 has dramatically broadened the scope of education targets, covering universal education from cradle to grave, both outside and inside structured schooling. Noticeably, number 4 is the only SDG with the word quality included. Quality is mentioned in the goal statement as well as in three of the goal’s targets. This is significant.

Yet how can we know if we have achieved these targets of quality? King expressed that the creation of relevant indicators continues to cause problems. He took SDG 4.1 as an example. The goal here is to “…ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes”. In indicator 4.1 this goal is measured by the “Proportion of children and young people at grade 2/3; end primary; end lower secondary, achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematics by sex”. Here, the term ‘free’ is given no mention in the indicator. King expressed that this did not portray the many sleepless nights lost by certain individuals who fought for ‘free’ education as part of SDG 4. Meanwhile, ‘quality’ is translated into “minimum proficiency” in just two subjects, a far smaller ambition. Furthermore, King explained that this reduction of ‘quality’ to ‘minimum proficiency’ contradicts other targets. For instance, a focus on just reading and maths (4.1) does not align sufficiently with ensuring “…that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development…” (4.7).

He then pointed out that alignment is not only necessary between SDG 4 indicators. The monitoring of SDG 4 is also expected to have interconnections with the 16 other SDGs. While SDG 4 aims to substantially increase “the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills… for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship” (4.4), SDG 8 seeks to “reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training” (8.6). This offers just one example of SDG 4 being linked to others, demonstrating the complexity of global governance by targets and indicators. Our speaker explained that such complexity also exists within the global governance architecture for monitoring SDG 4. He made clear that there is a vast range of expert bodies contributing to the implementation and measurement of SDG 4. King gave special mention to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), commending them for their work in this regard.

As a result of these complexities, delays have arisen. It was thought that the UN General Assembly would sign off on the global indicators in September 2016, however, this has not been possible. An inter-agency and expert group on SDG indicators cancelled their meeting in September 2016 and it is now suspected that it may be 2017 by the time the indicators are comprehensive enough to be signed off.

Finally, King discussed the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report in relation to quality education. He explained that the GEM Report is not only about formal education in schools, but about lifelong learning and the interrelations between education and the other 16 SDGs. This is covered in the report’s focus detailing of the 6 Ps: Planet, Prosperity, People, Peace, Place and Partnership. Quality education is paramount if countries are to prosper in these areas and SDG 4’s indicators are branded as unfit for purpose in this regard. The GEM report argues that ‘”quality cannot be reduced to learning outcomes” but should look at “policy, curricula, textbooks and teacher education”. King complimented this view.

He was however critical of one aspect of the GEM Report in relation to quality learning in technical and vocational education and training (TVET), emphasised in SDG 4. The GEM Report comments critically on the indicator for SDG 4.4 because it narrows the scope of TVET to just ICT skills. This critique is valid. However, the GEM Report corrects this by reviewing “general skills and not TVET skills” which King views as an error. He expressed that this approach goes the other way, rather than being too narrow it is too broad. Soft skills are difficult to define and measure, causing even more problems. The TVET terms were implemented deliberately and deserve to be upheld.

Despite this critique, King was complimentary of the GEM Report in his conclusions, believing it to be “a masterful analysis of the SDG ambitions and global realities”. Amongst these realities we must pay attention to the affordability of certain targets. King reiterated this during the Question and Answer session when asked “How can we increase countries’ capacities to report on indicators?” he replied with a convincing solution, suggesting that UN agencies and contractors could help build the capacity of national statistical offices to better understand targets and indicators. However, he admitted that this would likely be an expensive investment. And thus, the translation of SDG targets to effective indicators is an ongoing process.

Chapter 3: Link Community Development

Link Community Development is a small charity based in Edinburgh which works to improve the life-chances of those in some of the poorest countries in rural, sub-Saharan Africa.

Link operates through its five locally registered organisations in Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi and Uganda. Link works collaboratively with local governments to assist in the provision of quality education and supports formal education within the local school system. Account is taken of the resources available and the particular dynamics within each country. Since 1992, Link has supported over 3,000 rural schools and had an impact on around two million learners, community members, teachers and government education staff.

Link works to support SDG 4, however, as all SDGs are interconnected, it also supports SGD 5 (gender equality) and likely also has an impact on others. On the occasion of the GEM Report Launch on education, International Programme Director Dr. Samantha Ross outlined the situation with education in Ethiopia and the work that Link is doing to support its provision.

Despite strong enrolment figures in primary education, current trends reveal problems persist in the country’s educational system. Only 208 in 1,000 children enrolled actually complete primary education and generally with very poor achievements. The situation is aggravated by great disparity between rural and urban areas and marked gender inequality. Therefore, Ethiopia still faces huge challenges in delivering a quality education to all its children, but the situation is even harder for girls, as they are particularly oppressed – culturally, socially and economically. Domestic duties, early marriage, low status, menstruation and lack of role models are some of the problems which prevent girls from completing primary education.

Wolaita is one of the poorest rural areas in Ethiopia. Here, in order to improve girls’ enrolment, retention and performance, an ambitious project has been launched by Link, which consists of 38 activities and involves over 62,000 girls in 123 schools. Launched in partnership with the Ethiopian Ministry of Education and in alignment with its policy, the project costs only £46 per girl over project lifetime, thus increasing changes of scalability, sustainability and long-term change.

Results from midline assessment have proved the success of the project. Thanks to Link’s work, literacy and numeracy targets have been exceeded; gender disparities have decreased and girls’ interest in scientific subjects has increased. These results were achieved thanks to a range of effective activities, such as after school tutorials, teaching training and mentoring and leadership, and importantly, by boosting self-confidence. Link team found that it was crucial to support girls emotionally and practically in order to increase their self-confidence and to encourage them to remain in school. Some of the initiatives include guidance and counselling programmes in order to address this. The establishment of a Girls’ Education Advisory Committee and a Girls’ Club, which distribute sanitary pads and underwear and builds female toilets and sanitation rooms have helped girls feel safe and protected and in doing so begun to dismantle the taboo of menstruation.

Community support has been vital in helping schools improve and ensuring they are held to account. Communities have been invited to attended meetings to understand and discuss the improvements schools are making and monitoring proved to be an important way for the community to be involved. As a result, girls’ education has become more prominent in community conversation. This has also been achieved through local language films shown in rural communities: girls were taught how to make a one-minute film in which they could talk about the obstacles they faced in education, thus drawing attention of issues of importance to them.

In response to a question on how technology could help, Dr. Ross answered that it does not feature at the moment beyond government officials as the schools are in remote areas with limited or no access to electricity.

When asked about the sustainability of the programme, Dr. Ross was confident that the programme would carry on if Link was not able to continue their work in Ethiopia. As Link works with local governments and authorities, there are training initiatives and a transfer of skills continually taking place to ensure that the educational programmes continue to be implemented.

Dr. Ross concluded that the initiatives introduced in Ethiopia have proven to be very effective and that “educating women is at the heart of development”.

Conclusion

To achieve these goals, nations across the world have to innovate and devise smaller schemes to support the adaptation of the policies in different cultures and a range of rural, urban and isolated settings. Alasdair noted this when questioned as to the capacity of less developed nations to record and report national statistics on the progress of the 170 odd SDG indicators. He acknowledged that generating information was in itself an expensive process and that building capacity would be a challenge for many countries looking to collect domestic data.

We remain hopeful that the progress set out in the report will be achieved by 2030. As Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world”.